by Brooke Lieb

Alexander Technique teacher and author Pedro de Alcantara is celebrating the release of the 2nd edition of his popular book, "Indirect Procedures: A Musician’s Guide to the Alexander Technique," with ACAT! He will be discussing how his deepening understanding of the Alexander Technique in the sixteen years since the publication of the first edition has led to a substantial revision of the book in a free event open to all on Monday, November 10th. This will be followed by a weekend workshop, "Forward & Up: A Creative Approach: An experiential workshop for Musicians, Alexander Students and Alexander Teachers" on November 15th and 16th.

by Brooke Lieb

Alexander Technique teacher and author Pedro de Alcantara is celebrating the release of the 2nd edition of his popular book, "Indirect Procedures: A Musician’s Guide to the Alexander Technique," with ACAT! He will be discussing how his deepening understanding of the Alexander Technique in the sixteen years since the publication of the first edition has led to a substantial revision of the book in a free event open to all on Monday, November 10th. This will be followed by a weekend workshop, "Forward & Up: A Creative Approach: An experiential workshop for Musicians, Alexander Students and Alexander Teachers" on November 15th and 16th.

When did you first experience the Alexander Technique, and why did you decide to have private lessons?

I went to college at SUNY Purchase in Westchester. One of my cello teachers took lessons from Pearl Ausubel and suggested that I try the Alexander Technique to improve my coordination at the cello. I went along with his suggestion, not knowing what I was getting into!

What are some of your stand out memories from those initial private lessons?

Pearl was my first teacher, and I took infrequent but regular lessons from her for about two years. My memories of my very first lesson, in the fall of 1978, was the feeling of growing, growing, growing like a plant in a speeded-up stop-motion video clip. It was absolutely intoxicating.

Why did you decide to train; and how did you choose which course to join?

Lessons were having a deep effect, and I decided to see what would happen if I brought the Technique to the very center of my life. I trained with Patrick Macdonald and Shoshana Kaminitz in London, from 1983 to 1986. My motivation was partly to train with someone who had trained with Alexander himself, and partly to study the cello with a great London-based teacher, the late William Pleeth.

What was your inspiration for Indirect Procedures?

In the spring of 1990 I visited the pianist and composer Joan Panetti, one of my old music teachers at Yale (where I went after my undergrad studies at SUNY). She witnessed me in a somewhat directionless personal and professional transition, and she suggested that I write a book as a way forward. I’m of course very thankful for her insight regarding the merits of writing a book and my potentialities as a writer.

Tell us about the revised edition.

The first edition was published in 1997, but some of its concepts were borne of a research project I did while training back in 1985 and 1986. This is almost 30 years ago! Naturally enough I learned many things over the decades, and the old edition didn’t represent my convictions or my temperament anymore. I’d say the revised edition is actually a new book. You might want to check my essay “The Process of Change,” published in AmSat News, where I explain the book’s transformation.

What advice would you give to other Alexander Teachers to stay inspired and excited about their teaching?

Lessons are actually encounters in disguise—encounters with the “other,” who really is a mirror for you to learn about yourself; encounters with the unpredictable, the challenging, the entertaining. Years ago I actually stopped thinking of myself as a teacher, with the duties and constraints that the word implies. Now I think of myself as an informal researcher in the field of creativity and health; my students really are my partners and assistants, each bringing completely individual contributions to my explorations. It makes for a very gratifying professional life!

More information about Pedro de Alcantara can be found at his website.

To register for the free event on Monday 11/10 at 7pm, go here: An Evening with Pedro de Alcantara: “Indirect Procedures, New Edition: The Process of Change”

To register for the weekend workshop on Saturday 11/15 and Sunday 11/16, go here: Forward & Up: A Creative Approach: An experiential workshop for Musicians, Alexander Students and Alexander Teachers

Space is limited for both events, so be sure to register in advance to guarantee your place.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Brooke1web.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com[/author_info] [/author]

by John Austin

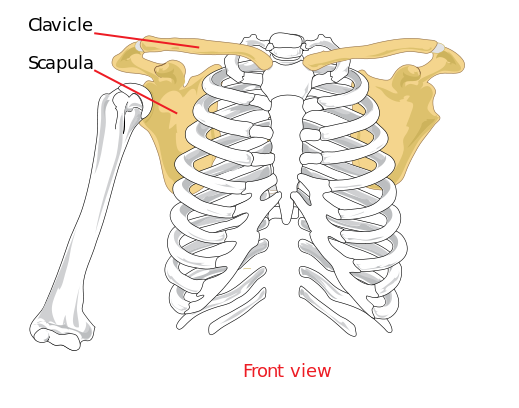

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

by John Austin

Finding neutral for the shoulders is one of the most challenging things one can do in terms of the use of the self in my experience. Add a complex activity that requires a certain level of ease in the shoulder girdle on top and you’ve got a recipe for paradox and frustration.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder.

Along the way to becoming a “serious” violist, I was told to keep my shoulders relaxed. So I went about figuring out how to do that. I am meticulous in the practice room and before long I had discovered that I could relax my left shoulder while playing although my right didn’t really follow suit. The static nature of the left shoulder in violin & viola playing allows for a certain amount of relaxation (release of all/most muscle tone) while the larger more dynamic movements of the bow require the arm muscles which originate in the back to be active for movement to occur. The left shoulder can relax even more if you use a shoulder rest as you then virtually never have to move your shoulder.

by Judy Stern

by Judy Stern

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Marjory Barlow was F. M. Alexander’s niece, who took lessons from him and trained under him to become an Alexander Technique teacher in 1933. She was the first person outside of F. M.’s Ashely Place Training course to start her own teacher training program. As a teacher she combines a no-nonsense, straightforward approach to the work with light-heartedness and compassion. Here she is in an interview from 1986.

by Witold Fitz-Simon

Marjory Barlow was F. M. Alexander’s niece, who took lessons from him and trained under him to become an Alexander Technique teacher in 1933. She was the first person outside of F. M.’s Ashely Place Training course to start her own teacher training program. As a teacher she combines a no-nonsense, straightforward approach to the work with light-heartedness and compassion. Here she is in an interview from 1986.