by Brooke Lieb

I have been taking lessons as a student of the Alexander Technique for over 33 years. I still take lessons to this day.

by Brooke Lieb

I have been taking lessons as a student of the Alexander Technique for over 33 years. I still take lessons to this day.

I began teaching 27 years ago, and have been training teachers for the last 25 years.

My greatest passion is training teachers, though I will take lessons for the rest of my life, and I get deep satisfaction teaching my private students.

I thought it would be useful to me, my students and the teachers-in-training that I work with, to consider what is different about each of these roles: student, teacher, teacher-trainer.

STUDENT

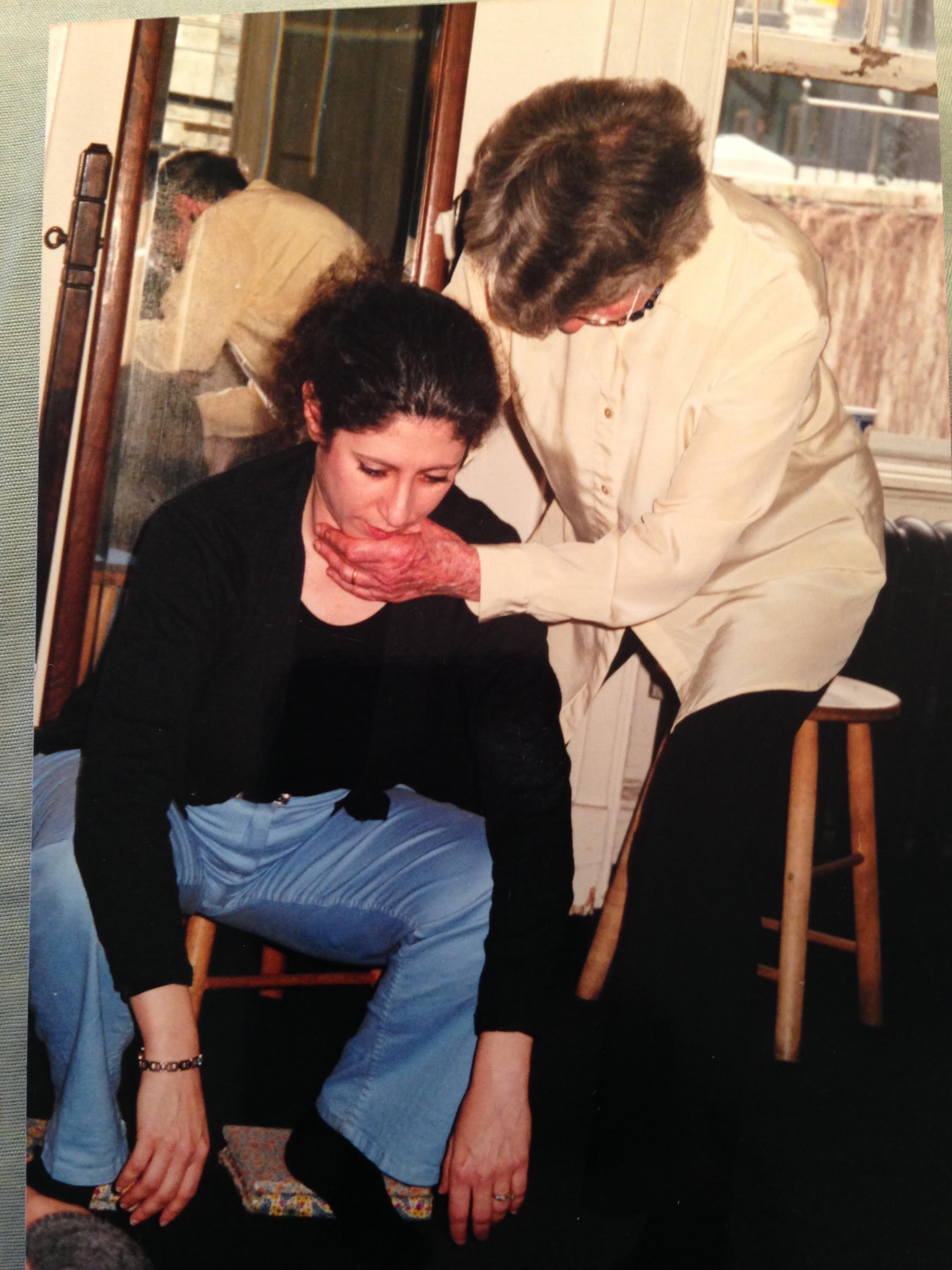

When I take a lesson, my attention is on myself. I gratefully accept the objectivity of my teacher as she uses her hands and words to engage me in learning. My learning takes place on many levels.

My teacher's hands are giving me information and experiences that assist my ability to observe and know how much excess tension I may be generating in my being. I am using my lessons to enhance the benefit I gain in my daily life when I bring my Alexander Technique tools to bear.

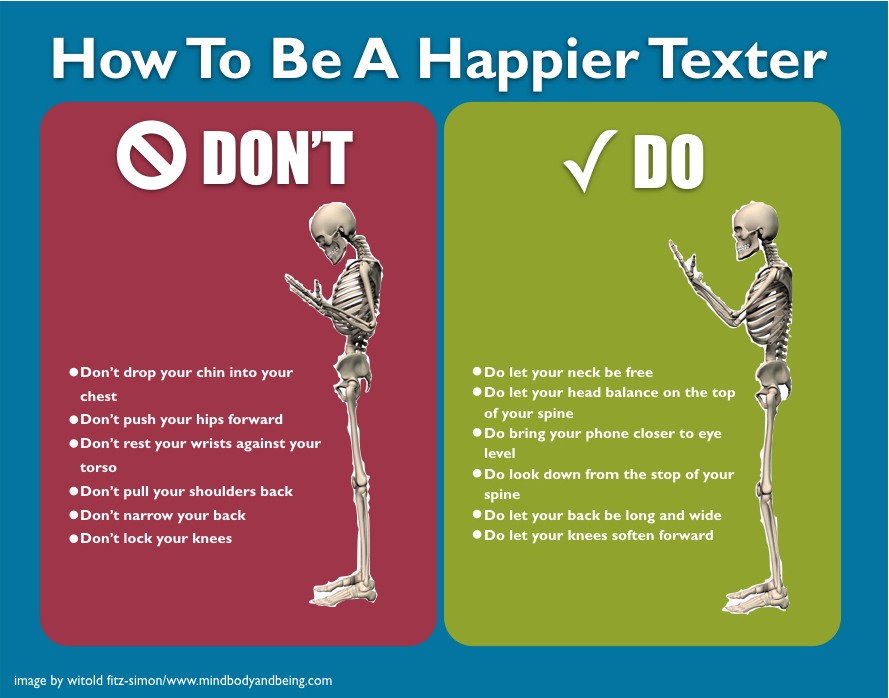

Sometimes the excess tension arises in response to a muscular demand, in activity, involving motion. We might explore how I carry out the activity of getting in and out of a chair, use my handheld device, or move into and out of downward dog during yoga practice.

I might observe excess tension in the context of my inner dialogue. Thinking about my workload, administrative tasks I have yet to complete, my response to someone's actions.

Any and every activity, mental or physical, can be material for the lesson.

Whatever I am exploring, I am interested in my own skills. I allow my teacher to be my guide and to educate me about myself and how I can best use my Alexander skills to access the efficiency and intelligence of being a human.

I have no focus whatsoever on assessing my teacher's use or process, I trust she is my guide. I am grateful and appreciative for the support and benefit I receive from the lesson and her teaching.

TEACHER

In contrast, when I am the teacher, my level of awareness is expanded to observe how my student is progressing, as I observe how I am teaching.

What skills might she benefit from learning or deepening during this lesson?

How can I use the hands-on component of the work to help guide her into a more integrated and poised state?

Private students (including me) take lessons for self-benefit, so they are focused on applying the Alexander principles to aid them in their lives. They are not planning to teach the work to anyone else. Their attention is NOT on the teacher.

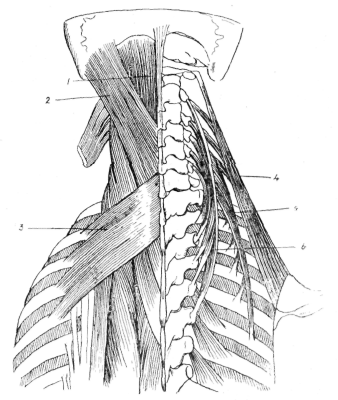

As the teacher, I manage my end-gaining, and apply the principles to myself in the activity of teaching (hands-on work; choosing where to put my hands; what concept I may emphasize in the moment or in the lesson; speaking; and utilizing instructional aids, such as pictures of anatomy and videos). I use Alexander's means-whereby to teach, i.e., I am using the very same skills I am teaching in order to teach effectively.

As a teacher, my attention is on my student, her goals for learning and applying Alexander Technique to solve her own problem. That dual attention leaves me less time to wander around in my own mental chatter, so teaching becomes an activity that supports me in inhibiting my own habits on multiple levels.

I also benefit directly in my own self from working with Alexander principles, even if I am the "teacher" in this situation. When I give a lesson, I get a lesson.

My work is as healthy and beneficial to me as it is to my student.

TEACHER TRAINER

In this role, I am adding a level of assessment for how self-sufficient the teacher-in-training (trainee) is when working on herself, and as she reaches a high level of competence, I assist her in applying her means-whereby to teaching.

On our training course at The American Center for the Alexander Technique (ACAT), our trainees regularly put hands on faculty members as a tool for training. This approach is educational on multiple levels:

1) Faculty members all have a high level of competence at applying means-whereby to activity, so in the same way we use our hands on our trainees to convey inhibition and direction, when our trainees put their hands on us, we are still transmitting that information through our whole bodies. As the trainee progresses through the three-year training, she recognizes what she is witnessing under her hands, and with her eyes and ears. She has worked with classmates, and practice students with less skill, and can compare and contrast what she has observed under her hands. This gives her a sense of the kind of changes and progress she may observe in her students, so she knows that learning and change really are happening over time.

2) When a trainee works on a faculty member, we give specific verbal and hands-on cues so the trainee can observe how a change in her system facilitates a change in the teacher she has hands on. Sometimes the change is towards enhanced poise and efficiency, sometimes the change is towards increased strain, effort or tension in muscle tone. Either way, observing the change allows the trainee to consider her own internal state, use her developed skills at self-work, and observe the change in the teacher-trainer she is working with. This is the means-whereby of teaching in action.

3) As the trainee works with faculty, she realizes we all have habits of use that interfere with our full potential for poise and efficient coordination. The trainee can provide valuable instruction to the trainer, and can also understand that a teacher's use need NOT be perfect for a teacher to be highly skilled and effective in our teaching.

I theorize that when a teacher has hands on and is working with her skills to inhibit and direct in herself in order to communicate that to her student, that process is discernable to the student. It may be so subtle the student is not yet aware of how the teacher's use is facilitating ease and poise, but the intention comes through. So even if the teacher is sometimes tightening her neck in moments, she is ALSO freeing her neck and using inhibition and awareness. That intention is picked up by the student, who is also providing inhibition and direction in the lesson. Student and teacher assist each other in this process. Both startle and pull down in moments, but both ALSO apply inhibition and direction to antidote startle and pull down.

In Closing

In some ways, the same means-whereby is in play in all three distinct roles, but there are clear differences in the short-term outcomes for learning and how this is accomplished in these three roles.

This post was originally published on brookelieb.com

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Brooke1web.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]N. BROOKE LIEB, Director of Teacher Certification since 2008, received her certification from ACAT in 1989, joined the faculty in 1992. Brooke has presented to 100s of people at numerous conferences, has taught at C. W. Post College, St. Rose College, Kutztown University, Pace University, The Actors Institute, The National Theatre Conservatory at the Denver Center for the Performing Arts, Dennison University, and Wagner College; and has made presentations for the Hospital for Special Surgery, the Scoliosis Foundation, and the Arthritis Foundation; Mercy College and Touro College, Departments of Physical Therapy; and Northern Westchester Hospital. Brooke maintains a teaching practice in NYC, specializing in working with people dealing with pain, back injuries and scoliosis; and performing artists. www.brookelieb.com[/author_info] [/author]

Experiential Anatomy and Alexander Techniquewith Witold Fitz-Simon

Experiential Anatomy and Alexander Techniquewith Witold Fitz-Simon by Brooke Lieb

*I recommend NOT riding the ferris wheel in the first place, but if you do find yourself having to manage your fear of heights, at least you might be able to ease some of the discomfort.

by Brooke Lieb

*I recommend NOT riding the ferris wheel in the first place, but if you do find yourself having to manage your fear of heights, at least you might be able to ease some of the discomfort. by Brooke Lieb

LIEB

by Brooke Lieb

LIEB by Brooke Lieb

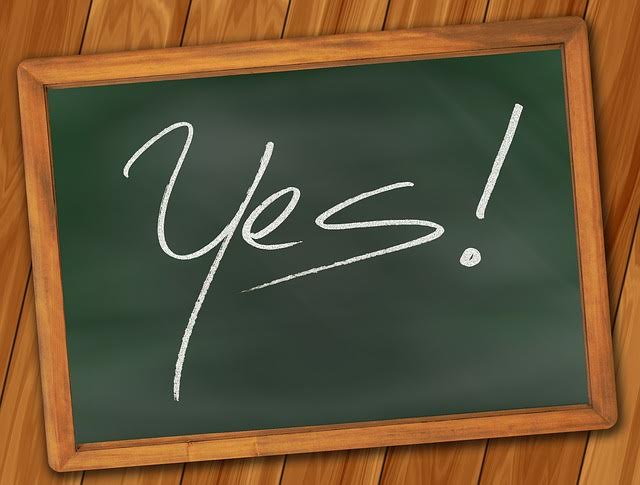

I have been involved in business and life coaching and spiritual communities that were all about being a yes. “Being a Yes” means looking on the positive side of things, going for it, not taking no for an answer, and with that, the dark underside of self recrimination, FOMO (fear of missing out), shame if I’m not being a yes, and the uncomfortable feeling that comes when you say yes in times when a “no” is more authentic.

by Brooke Lieb

I have been involved in business and life coaching and spiritual communities that were all about being a yes. “Being a Yes” means looking on the positive side of things, going for it, not taking no for an answer, and with that, the dark underside of self recrimination, FOMO (fear of missing out), shame if I’m not being a yes, and the uncomfortable feeling that comes when you say yes in times when a “no” is more authentic. by Brooke Lieb

Q. What, if anything, did you learn from putting hands on faculty?

by Brooke Lieb

Q. What, if anything, did you learn from putting hands on faculty? by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening.

by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening. by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification.

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification. by Anastasia Pridlides

by Anastasia Pridlides by Patty de Llosa

by Patty de Llosa by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis!

by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis! by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands. by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.

by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.