by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

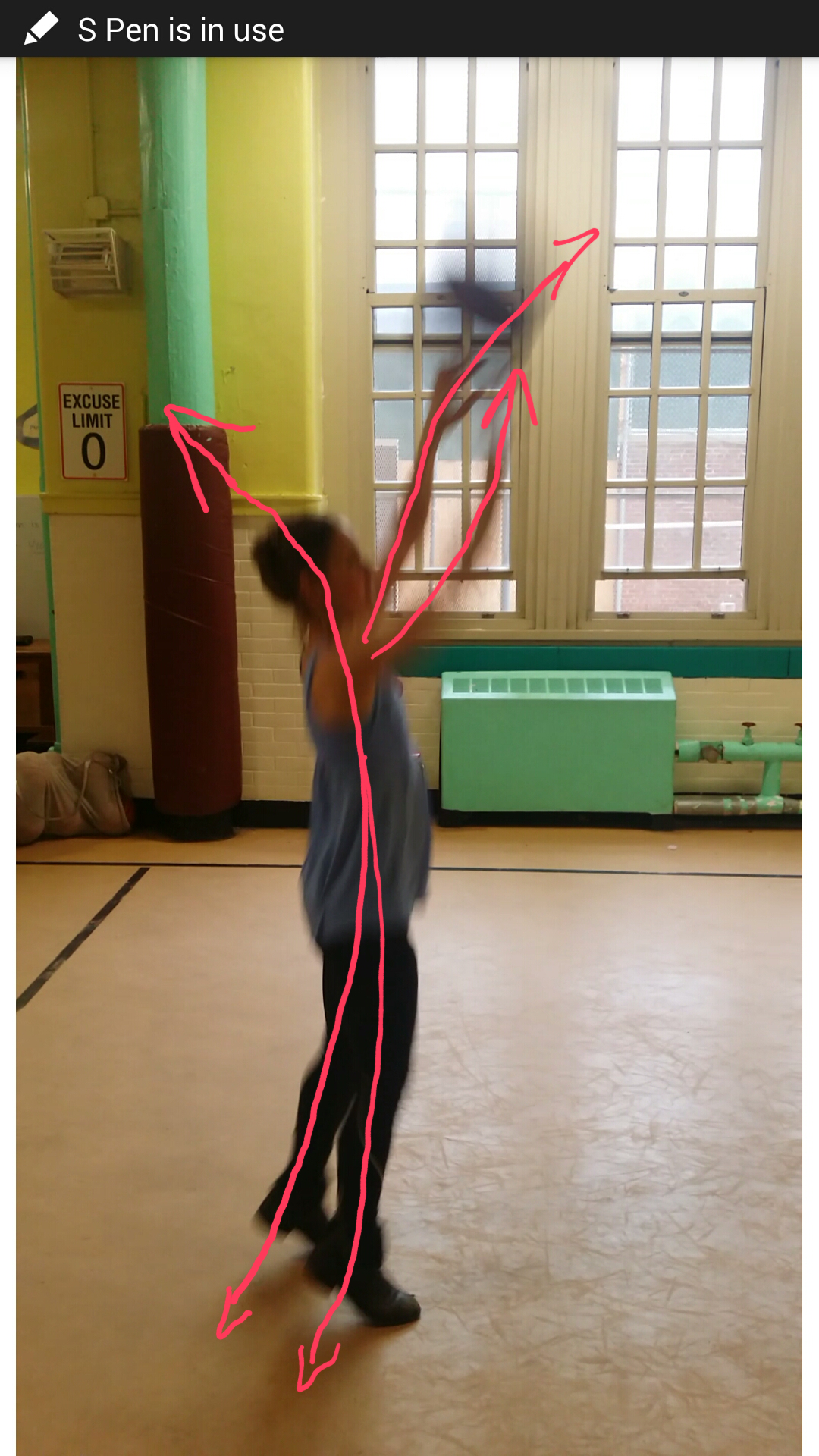

For a lot of people, sexual intimacy is an attempt to return to our bodies and feel whole. We spend so much time in our heads, experiencing life not fully in our bodies, not feeling the integration of our system. There is so much fixation on finding a partner and experiencing intimacy as a way to feel connected and validated. Through Alexander Technique we practice feeling whole so that we don’t need to be in our front bodies grasping for more. We can be aware of our back bodies, our head moving forward and up, neck free, torso widening and deepening, knees moving forward and away. All of the parts create a simultaneous awareness of the whole: one at a time and all together.

A lot of the pain I experience in life comes from a feeling of being disconnected and isolated. There’s a quote I love by Lawrence LeShan, “It is the splits within the self that make for the feeling of being cut off from the rest of existence.” I am slowly learning how to experience myself without all the splits -- to gather all my different sides --shawdowed and bright -- and hold them into a unified whole.

This past winter I was severely depressed and felt as if my Self were fragmented into tiny meaningless pieces. I felt alone in my head, and disconnected from myself, loved ones, or any purposeful connection. My mind was full of vicious and self-loathing thoughts, and I tried to escape the abuse by fleeing from my body and myself and towards someone I was romantically interested in. I have learned, again and again though, that true resolution comes from staying -- creating space for the pain, witnessing it, holding it, and integrating it into my whole self. If I try to reach outside of myself to escape pain, that only takes me further from home.

I recently took a course on Visceral Manipulation, taught by Liz Gaggini. We learned that in order to heal a client’s organ, you must have an attitude of nonchalance and only put some of your attention on the person. The rest of your attention will stay in your body, in the room around you, and beyond. In order to heal another, you must stay whole. If you give too much, you offer the person a fragmented presence, an energy that is coming just from the front of the body -- a grasping, an end-gaining.

This is so true for relationships. When connecting with another person, even someone to whom I’m greatly attracted, I can practice not coming forward into the pull of hormones and craving, but remain in my full body. There is much pleasure to feel just here as I am, inside myself. This is a new and exciting practice, to realize that simply walking around and being inside my body can feel good, especially after the last 5 years of chronic pain and health problems. I am learning how to hold pain as part of the experience, not the only thing. I am learning to accept all the parts of myself, and to hold them in an awareness that is deep and fulfilling.

This past winter I liked someone so much that I lost my awareness of my back body. I fell forward. I fell hard.

And the ironic thing is, I was leaning forward in order to feel a connection -- to return home. But home is back and up into my torso, widening and deepening, my head moving forward and up, my gaze softening, my neck being free.

Here I am again, having remembered, but life is a process of forgetting and remembering, of getting lost in the pieces, and then expanding our awareness to perceive more. Alexander Technique is the gentle practice each day to return to our whole.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/helsinki-sun-headshot.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]MARIEL BERGER is a composer, pianist, singer, teacher, writer, and activist living in Brooklyn, NY. She currently writes for Tom Tom Magazine which features women drummers, and her personal essays have been featured on the Body Is Not An Apology website. Mariel curates a monthly concert series promoting women, queer, trans, and gender-non-conforming musicians and artists. She gets her biggest inspiration from her young music students who teach her how to be gentle, patient, joyful, and curious. You can hear her music and read her writing at: marielberger.com[/author_info] [/author]

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification.

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification. by Anastasia Pridlides

by Anastasia Pridlides by Patty de Llosa

by Patty de Llosa by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis!

by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis! by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands. by Dan Cayer

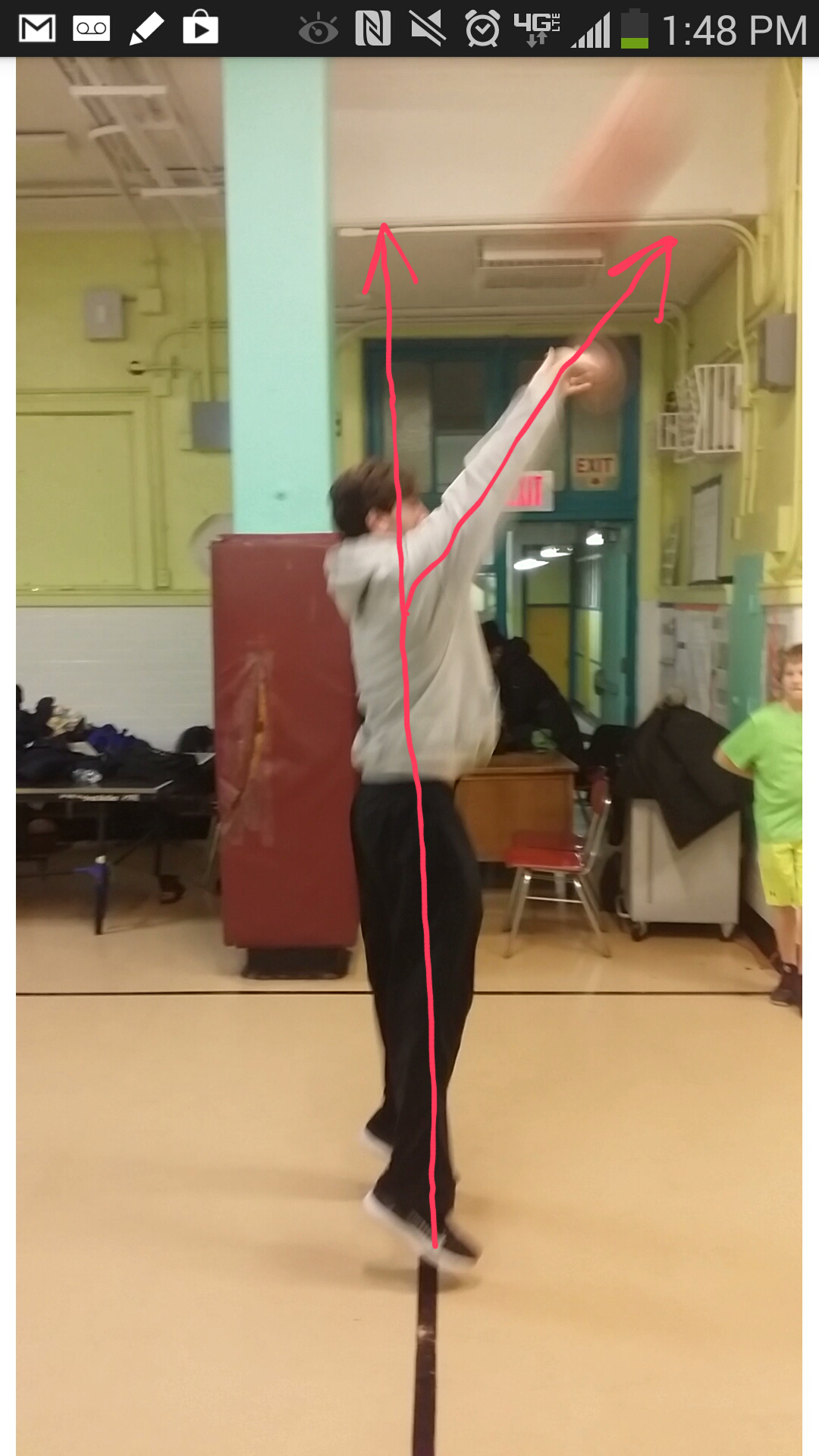

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.

by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school. by Emily Faulkner

by Emily Faulkner

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian.

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian. by Brooke Lieb

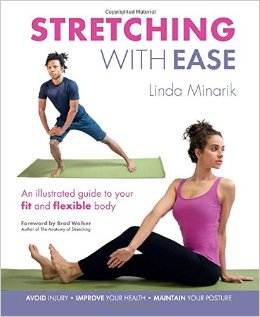

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®.

by Brooke Lieb

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®. By Jeffrey Glazer

By Jeffrey Glazer by Cate McNider

by Cate McNider

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb