by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening.

by Ezra Bershatsky

It is almost irresistible to become fascinated with the philosophies that are so perfectly compatible with the Alexander Technique; to revel in the Zen-like mysticism it inspires: “The chair lifts; I don’t lift it," or "I am breathed." For some, this is confirmation of what they already believe. However, I think this only serves to obscure for others and even ourselves what is actually happening.

This topic is of especial interest to me as I have found a wealth of knowledge in the Tao Te Ching: “Wei wu wei,” or “doing without doing,” is a prevalent theme throughout the text, and it offers considerable insight into various implications of The Alexander Technique. As pointed out by Walter Carrington, we cannot lead a life of non-doing, as we would inevitably starve to death. Carrington says that muscular activity in the body is obviously doing; however, to me this is anything but obvious. Would anyone say, “I’m doing my heartbeat?” Another way to define “doing” is as any volitional or potentially volitional muscular response. I say potentially, as the vast majority of muscular responses and coordinations are allocated unconsciously by the brain through the stimulus of a desired outcome.

Doing without doing is a way of accomplishing an end while avoiding an habitual means to obtain it. This might be achieved by changing one's immediate intention, thus delaying the ultimate outcome. For instance, if my goal is to sit in a chair, I can decide merely to sit, which would trigger a complex muscular coordination involving hundreds of muscles contracting and releasing simultaneously and sequentially. My desire to quickly carry out the action of sitting might allow for little new input into achieving the action, so that if the chair is lower than the average chair, I will probably fall into it, expecting to have been sitting sooner. If I wanted to employ a "non-doing" approach, I could first try to have my desire to sit become the outcome of another intention: my knees bending. If I continuously bend my knees, eventually I will make contact with the chair. Such an exercise would begin to reeducate me from my habitual way of sitting, so that when next I go to sit in a "doing" or habitual manner, it might happen more efficiently. It should be said that this improvement will most likely revert quickly to my more habitual behavior shortly thereafter, unless this type of work continues.

It is our goal to accomplish any end by finding a way to allow a spontaneous coordination instead of imposing one; to consider how this action will be achieved instead of predetermining it; to avoid habitual response patterns and allow for spontaneous ones, even if the latter are at first clumsy or less efficient. Once we have established clarity about this goal, the implications for similar or seemingly related philosophies and mystical ideas can be safely considered, and will not be conflated with the principles and workings of the Alexander Technique.

[author] [author_image timthumb='on']http://www.acatnyc.org/main/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Ezra-Bershatsky-by-Sandro-Lamberti-Photography-23.jpg[/author_image] [author_info]EZRA BERSHATSKY—A graduate of The Juilliard School Pre-College Division, Ezra has two Bachelor degrees of Music from Mannes College The New School for Music, in vocal performance and musical composition. He is currently training to be a teacher of the Alexander Technique. He has been singing and performing since childhood, and early in his training he discovered that he has a passion not only for making music, but for teaching others. Ezra teaches voice in New York City on the upper west side. [/author_info] [/author]

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb by Mariel Berger

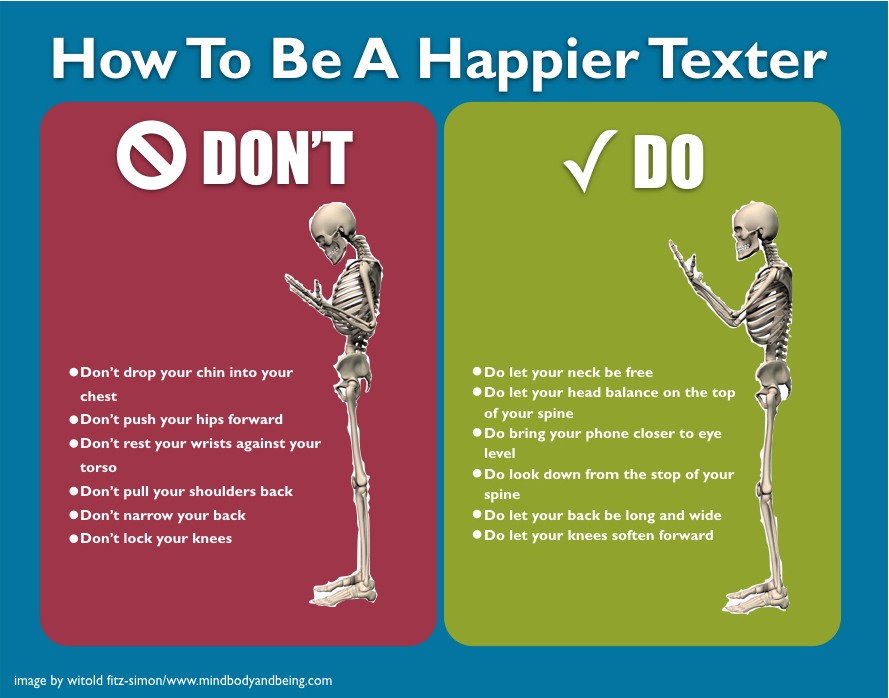

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Mariel Berger

Many thanks to my Alexander Technique teachers: Witold Fitz-Simon and Jane Dorlester.

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification.

by Brooke Lieb, ACAT Training Director

ACAT’s Teacher Certification Program follows a developmental curriculum, which has been refined over the last 49 years. Our program is designed so that our graduates are prepared, and more importantly, are confident about their ability to teach, by the time they receive their teaching certification. by Anastasia Pridlides

by Anastasia Pridlides by Patty de Llosa

by Patty de Llosa by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis!

by Emily Faulkner

This past February, I had the good fortune to travel to the Alps to take Erik Bendix’ one week Ease on Skis workshop. I am a passionate skier, and not too bad at it, but having started skiing late in life, I am always frustrated by how slowly I seem to progress and how hampered I am by fear. As a dancer, I love to move. The technique of skiing - the rhythm and the fluid motion – is magical when it comes together, but frustratingly elusive. As soon as I approach a pitch that seems too steep, a patch of ice, or some unexpected bumps, fear takes over, my technique goes out the window, and skiing becomes a matter of survival instead of joy. The Alexander Technique is, of course, the perfect medium by which to analyze fear and response. Enter Ease on Skis! by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Patty de Llosa

Hurrying speeds us away from the present moment, expressing a wish to be in the future because we think we’re going to be late. To counter it, Master Alexander teacher Walter Carrington told his students to repeat each time they begin an action: “I have time.” He tells us that on his visit to the Spanish Riding School of Vienna, where horses and riders are trained to move in unison, the director ordered the circling students to break into a canter, adding, “What do you say, gentlemen?” And they all replied together, “I have time.” Try it yourself sometime when you’re in a hurry. Send yourself a message to delay action for a nano-second before jumping into the fray.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands.

by Brooke Lieb

When I was taking private lessons, I had no idea how my teacher was facilitating changes in my sense of ease and freedom, I just knew it was different from anything I had ever experienced. I recognized some of it was what what she told me to think and wish for, but it seemed most of the changes were the result of some mysterious and magical quality in her hands. by Dan Cayer

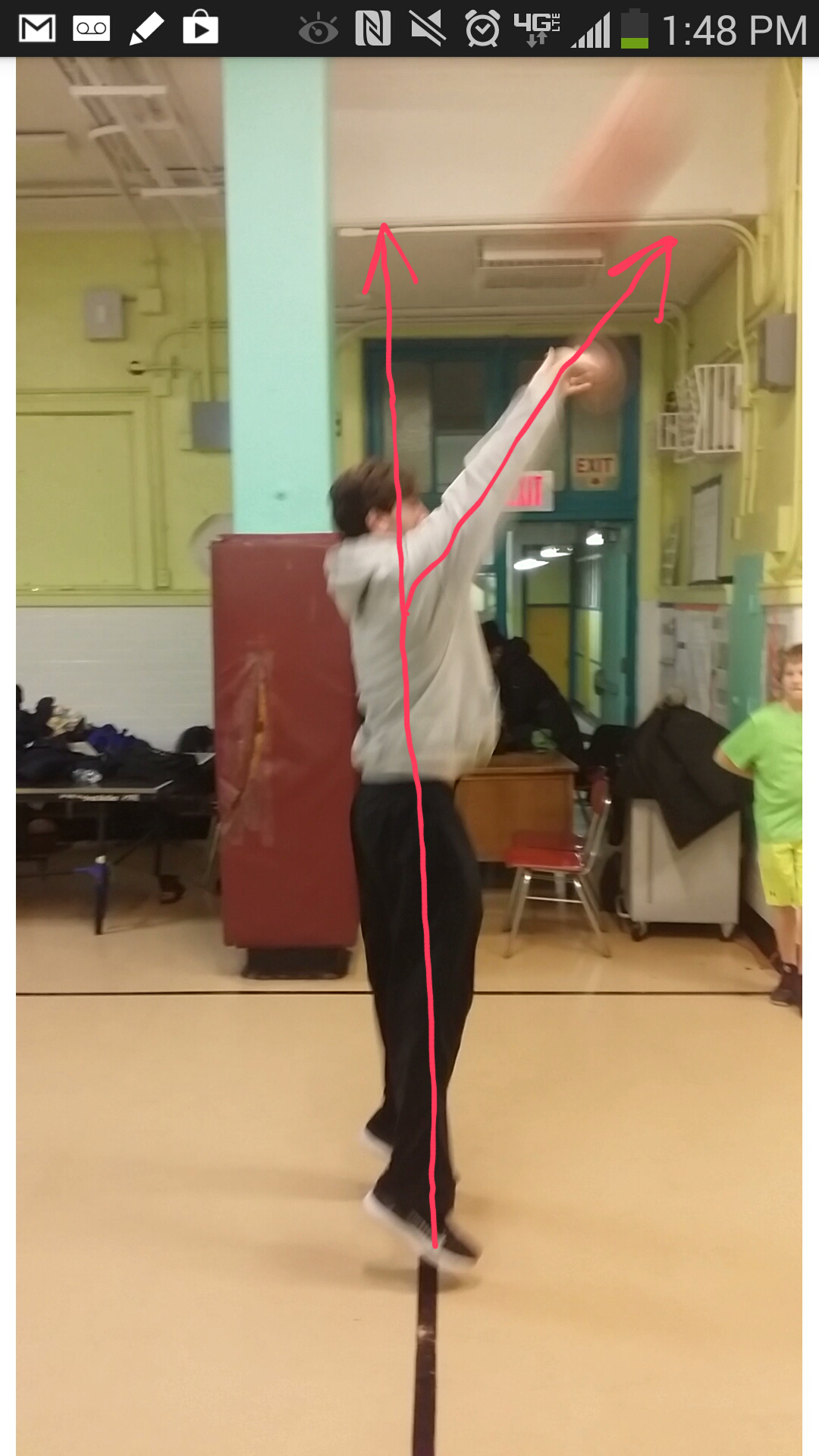

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school.

by Dan Cayer

A couple years ago, a quiet 17-year-old who I’ll call Len, was referred to me by his mother for a course of Alexander Technique lessons. She had heard that the AT could improve his posture and help him focus. Nearly 6’4” – and still growing – he stood and sat with a pronounced slump, which was likely contributing to back pain. His mother also suspected that his slouch was, partially, an attempt to not “stick out” at school. by Emily Faulkner

by Emily Faulkner

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

by Karen Krueger

Many Alexander Technique teachers don't like to even mention the word "posture." They think the very word has so many wrong connotations that it should be avoided. But I take Humpty Dumpty's point of view: the important thing is not what people think a word might mean, but what we say it means:

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian.

by Karen Krueger

I've been reading a lot lately about "vocal fry," a speaking mannerism that some people find extremely annoying and others defend as an innovative trend among influential young women. Vocal fry is a gravelly or creaky sound to the voice that is most clearly heard at the ends of words and phrases. Some people call it "the NPR voice." Others trace it to Kim Kardashian. by Brooke Lieb

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®.

by Brooke Lieb

Linda Minarik is a pianist, dancer, singer, and fitness professional. Her new book is entitled Stretching with Ease. Linda has been familiar with the Alexander Technique for nearly 40 years. Her first private lessons were with ACAT alumna Linda Babits in connection with practicing piano with ease. Linda’s life-long love of movement inspired her to train in ballet, and to become a certified group fitness instructor, including teaching qualifications in Gyrokinesis® and the MELT Method®. By Jeffrey Glazer

By Jeffrey Glazer